Wednesday 17 April, 2024

Aussie engineer and inventor Dael Liddicoat has been back in Gisborne “training the trainers” to operate the lightweight deployable water desalination purification systems he’s created for the Tairāwhiti region.

Tairāwhiti Emergency Management (TEMO) group manager Ben Green says they’re a critical component of the Tairawhiti emergency planning for communities so they can be self-sufficient to treat water if they’re impacted by a catastrophic emergency scenario.

TEMO has just received six units for large community centres as part of the Marae Emergency and Preparedness Project which is based on critical risk-based planning to support isolated communities so they can initiate and lead their own response to, and recover from, a catastrophic event. Nineteen containers have been distributed through the project with specialist emergency equipment including a mass casualty first aid kit, hybrid solar power unit, water treatment kit and more.

A further 15 desalination units have been ordered by Ngāti Porou Taiao.

When it came to sourcing a water purifying kit that can treat seawater, Mr Green says they were thin on the ground.

When he connected with Mr Liddicoat in 2021, the appeal of the prototype he had developed met what was being sought for Mr Green’s project in Tairāwhiti.

The design brief was that the unit had to be portable, in a Hilux or Hughes 500 helicopter, and that the system could operate with the hybrid power systems that Mr Green had another developer working on.

Fast forward to today and the region will now have more desalination equipment capability than what can be deployed nationally.

With both Mr Green and Mr Liddicoat having served in the military and been deployed into austere environments around the world, the ability to configure the equipment and refine the user requirement was easy.

“Dael is an exceptional engineer and what was a concept he developed is now an operational system that we are deploying across the region,” said Mr Green.

Mr Liddicoat’s AquaGen system has been customised for Tairāwhiti.

It’s a three-stage system that clarifies the water, purifies then puts it through a UV sterilisation phase to make sure it’s fit for consumption. The pre-filter is set up to deal with water sources that may be filled with sediment, from rivers or treat seawater.

It all started when Mr Liddicoat was posted with an aviation unit to Townsville, Australia, during the 2019 floods. One of the key tasks was loading pallets of water and shipping them by helicopter to communities.

“It became very expensive water,” says Mr Liddicoat.

“We were using a product to de-mineralise water to clean the helicopter engine and people were asking why it couldn’t be used for personal consumption.”

The rest is history. The Brisbane-based company produces a small range of water purifiers and desalination units, with ongoing research and development to ensure fit for use.

“The best thing about these ones here (in Tairāwhiti) is that they’re built into a military-style trunk, and you can chuck them into the back of a Hilux to get them out to communities,” says the aeronautical engineer.

“They operate self-sufficiently – you just put the hose in the water and off you go. The idea is so that people can approach the kit, having never seen it, follow the steps and turn it on and run it.”

His training trip to Tairāwhiti was as much about that as it was about getting feedback from the TEMO team.

Mr Green is now working with Mr Liddicoat to develop larger-scale units that can support urban populations when there has been a total loss of water infrastructure.

“The loss of the primary city water supply in Cyclone Gabrielle validates the concept and development of the units now being deployed, however we need to configure a system that has capacity to deal with population density,” says Mr Green.

“The ability to treat and supply water to displaced people is similar to how refugee camps are set up.”

The current units can treat up to 250 litres an hour from a contaminated freshwater source, and about 90 litres per hour of seawater.

Mr Liddicoat is working with similar groups in Australia around prevention and preparedness.

“We are taking a lot of learnt lessons around what has happened in New Zealand and Tairāwhiti specifically, and preparing for that, focusing on systems that can cope for a dirtier than normal environment.”

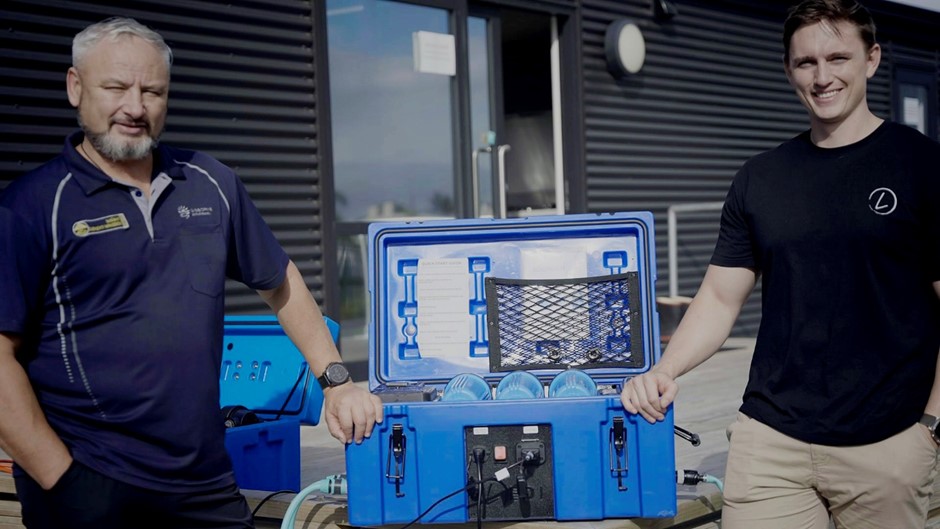

Tairāwhiti Emergency Group manager Ben Green with LEDI AquaGen desalination system designer Dael Liddicoat and one of the Australian developed units that is being distributed across Tairāwhiti to ensure small remote communities can be self-sufficient following a catastrophic event. Photo by Kumeroa Papuni-Tuhaka